This story was written from the point of view of David Mihalyfy, PA at The Selfhelp Home.

In religious studies — that is, the academic study of religion, through such lenses as anthropology, sociology, and history — the weekend before Thanksgiving is always AAR-SBL, the annual conference of the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature.

This past November it was in San Diego. I spent the week, however, in Germany, experiencing a rather different sort of history than can be found in the drab rooms of sprawling convention centers.

I’ve attended AAR-SBL in years past and even presented. (Elevator pitch: my research showed how the rise of the historical Jesus took root in the 19th-century United States less among professors and ministers proficient in Greek, and more among fringe figures like the hypnotist who described seal-like creatures on Jupiter and specified how long Jesus lay in the manger.) But my connection to that world has faded as I chose to pursue other things than an academic career.

Even apart from how more than 70% of college faculty are non-tenure-track, factors like aging parents and a protracted degree program due to faculty bullying made me seek meaningful work elsewhere. Serendipity led me to jobs assisting the elderly and persons with disabilities, and now a position at the Selfhelp Home, which began in 1938 as an immigrant mutual aid society for elderly German-speaking Jews fleeing persecution in Central Europe.

Through the Selfhelp Home, I became acquainted with 97-year-old resident Fritz Cohen, who fled the German town of Ronnenberg in 1938 with his parents. He began making return visits to his hometown as soon as the 1950s, and took part in conversations and commemoration efforts as they evolved over the decades. And in November 2019, he embarked on a weeklong trip to Ronnenberg, which centered on two days of events reckoning with the town’s Jewish history and the legacy of the Holocaust. Fritz was accompanied by his daughter, and by me.

The main event was the laying of twenty-two “Stolpersteine” memorial bricks before each home where Jews had fled, joining three bricks which had already been laid in remembrance of Jews who were deported and murdered, including Fritz’s grandmother.

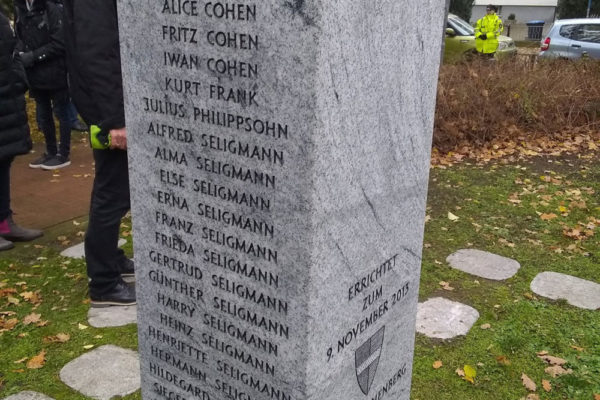

After speeches at different locations, including a former house synagogue now being proposed as an educational space, attendees ended the day opposite the Jewish cemetery, where flowers were laid at the foot of a memorial column listing the fates of the Jewish population.

The next day, Ronnenberg’s Lutheran church hosted a concert featuring works by less-remembered German Jewish composers of the Romantic era.

There were many people who made the weekend possible. Cologne artist Gunter Demnig began the Stolpersteine (which literally means “stumbling stones,” or stumbling blocks) project in 1992, and since then more than 70,000 have been laid worldwide. Ronnenberg residents Peter Hertel and Christiane Buddenberg-Hertel have spent countless hours rigorously documenting the town’s Jewish history, with the local government covering archival travel expenses and sponsoring the publication of their findings as a book. Local musicians are dedicated to reviving the region’s forgotten Jewish repertoire.

There were many in attendance: Fritz and his daughter and I, of course, but also the relatives of others who were persecuted, and easily fifty to sixty more, including high school students, businesspeople, and the Lutheran school superintendent. Some attendees, including journalists, recorded the event and helped spread knowledge of it even further.

Nor was the remembrance contained to this particular ceremony. The historians Peter and Christiane have conducted school presentations, teaching the fate of Ronnenberg’s Jews and opening up conversations about present-day xenophobia. Partway through the installation ceremony, the Lutheran superintendent in attendance left for a protest in nearby Hannover, where thousands marched against Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), a recent extremist political party known for its anti-Semitism. On a daytrip to the town of Celle, I saw similar documentation efforts at the synagogue there, and more Stolpersteine strewn on the city’s streets.

What of “history,” though? Certainly, in academic history, local examples of larger-known events can further conversations among professional scholars. But history can do work more important than that — showing what happened where people lived and live; fulfilling a responsibility to the past as well as the present. The Ronnenberg historian Christiane, for example, recalls how in the 1960s her history textbooks skipped from the 1920s to the Second World War, and she had to find answers about those decades from the local library and books like Anne Frank’s diary.

What most surprised me about my trip to Germany was how much more it spoke to the parts of myself that were nurtured outside of the academy than within it: the Chicago Sinfonietta’s performances of works by female composers, or seeing the fruition of a campaign by the Illinois League of Women Voters to rename a downtown Chicago street for suffragist and lynching investigative journalist Ida B. Wells, or the protests against immigrant family separation policies where I ran into other Selfhelp staffers, resident family members, and a couple of old coworkers from a library unionization drive — who as Jews were raised to say “Never Again” to any dehumanizing persecution.

From art to civic action to work, the past is what surrounds us and what always could be. The question is not whether we will acknowledge the past — it’s which past we will choose to acknowledge.